[Updated 2 Jan 2024 – Minor readability changes, Table of contents added]

Contents

- Contents

- Introduction

- The Working Group and the role of Defra

- The Natural England ‘Chichester Harbour Condition Review’

- The Royal HaskoningDHV report

- Let’s take a step back

- Chichester Harbour Investment and Adaptation Plan

- Thinking outside the box

- In summary

Introduction

I’ve spent a few hours over the past couple of weeks mulling over 12 December’s ‘Langstone Sea Wall’ drop-in event at the Plaza; an opportunity for local concerned residents to meet with representatives of the ‘Langstone Sea Wall Working Group’. The group was convened in 2022, comprising the Chichester Harbour Conservancy (CHC), Coastal Partners, and Hampshire County Council, with Natural England and the Environment Agency acting ‘in a supporting role’.

The session had been proposed at the November meeting of the Chichester Harbour Conservancy, during which a paper summarising the background to the Working Group had been discussed. In describing the Langstone sea wall situation, the paper notes that “It is an interesting case study of recreational access, nature conservation, differing levels of environmental designation, the inherent values placed on the location, the interpretation of information, facts and beliefs, the use of social media, and the challenges of rolling back a coastal footpath.”

This led me to re-read the Natural England ‘Chichester Harbour Condition Review’ published in 2021 but based on investigations carried out in 2019 which used key data sources from a previous decade. This was the document which had sparked the current discussions on the future of the sea wall at the Wade Court paddock and the millpond dam wall at Langstone. It’s worth re-reading all the material, particularly with reference to more recently available data.

In this post, I’ll cover some of the wider questions raised by the drop-in event, adding a few other thoughts triggered by discussion with working group representatives and supplemented by my own research and understanding of the situation.

The event was well-staffed by officers and elected members of the local authorities, including Lyall Cairns for Coastal Partners, Richard Austin for the Chichester Harbour Conservancy and Councillors Lulu Bowerman, Jackie Branson, Richard Kennett, Gillian Harris, Grainne Rason and Phil Munday.

Ian Walton represented the Environment Agency and while I missed Alison Marlow (?), the representative from Natural England, I’ve been told that she was approachable and attentive to the residents while reasserting her stance that the body ‘will concentrate on its brief to protect and improve the harbour’. She reportedly gave the impression was that she was not opposed to repairs being done to the Millpond wall, but awaited a formal proposal from the Councils before making any official comment or decision.

Like so many other important public consultation events, just 71 visitors were reported by CHC at the 12 December drop-in, hardly the ‘well-attended’ session that was described. That number included ‘the usual suspects’ from Langstone Village Association, Langstone Residents Association and Havant Civic Society, joined throughout the afternoon by a few other interested residents alerted by the advance publicity on the websites and Facebook pages for both HBC and HCS.

The Working Group and the role of Defra

The Environment Agency and Natural England are ‘executive non-departmental public bodies’ sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), representing the directives of central government to the working group. The two affected local authorities, Havant Borough Council and Hampshire County Council, are represented on the working group by their elected council members however direct representation from concerned residents’ associations has not been sought. Despite their greater knowledge and experience of the location, Coastal Partners and CHC are taking direction from the two Defra bodies and appear reluctant to bring practical challenge to the central government guidance so rather than ‘acting in a supporting role’, the impression given to the residents is that the Defra quangos are actually calling the shots.

Natural England’s focus has been on the ‘unhealthy and declining’ state of the Chichester Harbour SSSI and so it was interesting to hear a comment from the Coastal Partners representative that Langstone Harbour is acknowledged to be in far worse environmental condition than Chichester Harbour. Defra’s publicly available data actually shows Langstone in a better state than Chichester, ‘unfavourable but improving’, suggesting that the two environmental bodies may not be as well-informed as the local authorities on the ground here, probably more a reflection on a shortage of funding and resources rather than on any lack of skills and experience. In the case of the Environment Agency, press reporting has certainly exposed its inability to resource the policing of pollution into the inland rivers and waterways which is, of course, a significant contributory factor to the health of our two harbours.

The Natural England ‘Chichester Harbour Condition Review’

The current discussion was initiated by recommendations made in Natural England’s Chichester Harbour Condition Review, conducted during 2019 with a report published in February 2021. With all documents of this type, the vocabulary and style is necessarily technical so the ‘Executive Summary’ is particularly important for the casual reader. We cannot know how far into its 187 pages that decision-making elected councillors have read, but we can probably assume that few will have read much beyond the executive summary which included among its eleven recommendations, the following:

2) “Remove barriers to coastal change caused from inappropriate coastal management including coastal squeeze, which are resulting in saltmarsh erosion and interrupting sediment supply.”

4) “Maintain current actions and identify additional measures to reduce nitrogen into the harbour and the wider Solent including, depending on source apportionment, reducing nitrogen inputs from urban and rural diffuse (planning and farming), from atmospheric deposition and from point sources (mainly wastewater treatment works).”

‘Speed-readers’ could easily take the first phrase of that first recommendation literally, accepting in error that the removal of the existing wall to the path south of the paddock would directly improve the health of the harbour. As far as the second recommendation goes, most councillors, already exhausted by recent debate over ‘nitrogen neutrality’, will not have gone beyond the first part, missing the comment in parentheses at the end of the sentence.

Given the importance attached to the subject of ‘coastal squeeze’, the reader might expect it to be more prominent in the document than it actually is, right up there with pollution from the water treatment plants.

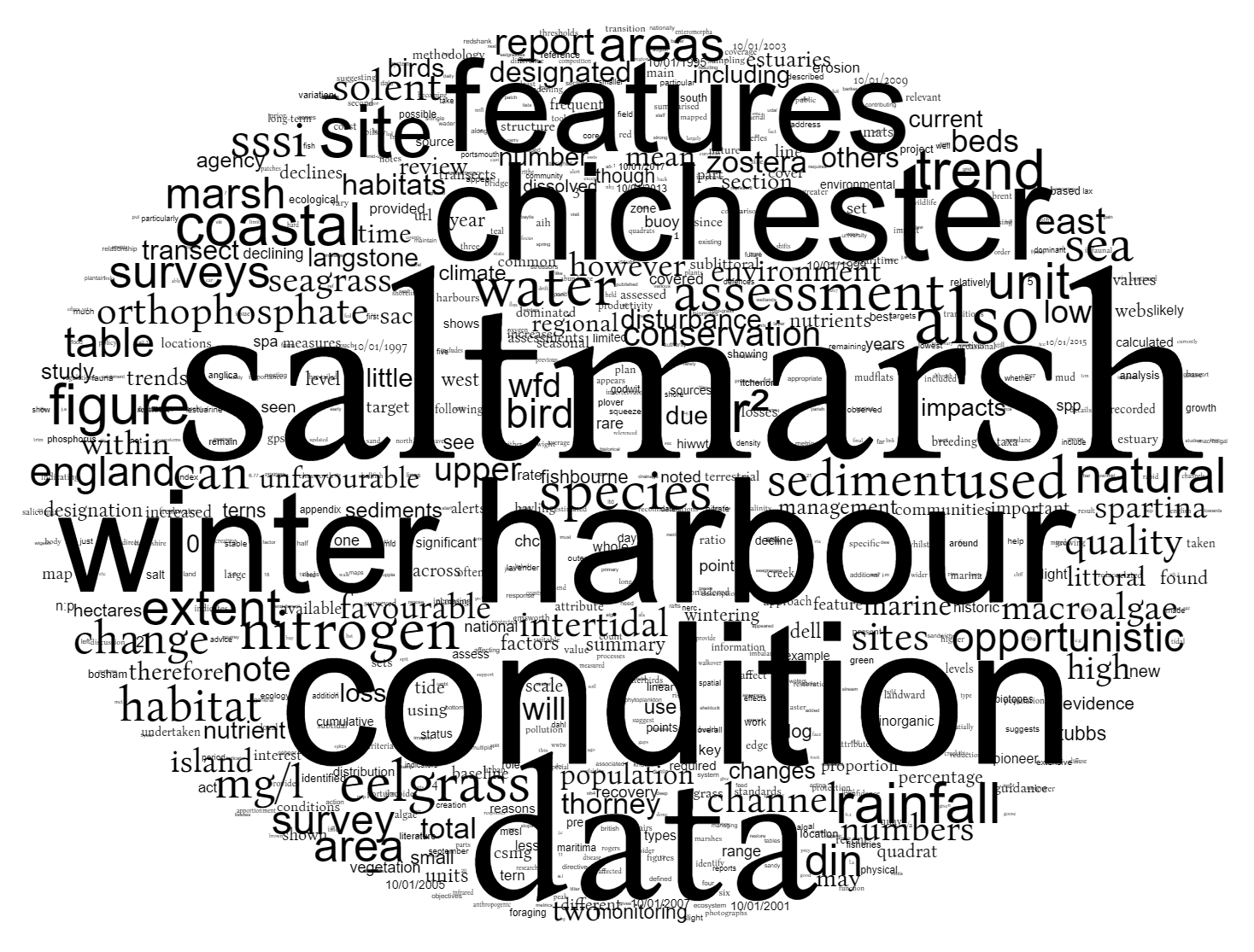

Constructing a simple word cloud from the text of the document may seem rather glib, but it does help to illustrate a point. The representation of thirty instances of the word ‘squeeze’ is just about visible on this chart, while the single instances of ‘effluent’ and ‘sewage’, together with just three instances of ‘sewerage’, are not. While coastal squeeze is indeed discussed a few times throughout the document, the attention given in the study to the impact of pollution from the catchment area is minimal.

The nitrogen source apportionment data shown in the Condition Review report at table 9.2 and relating to Southern Water’s Wastewater Treatment Works at Lavant, Chichester and Thornham is more than a decade old. Based on the Environment Agency’s own more recent data, Southern Water’s sewage discharges into Chichester Harbour at these and other locations, for example Sanitary Sewer Overflows (SSOs) at Bosham and Nutbourne, have recently been found to be excessive, demonstrating that the harbour now shares, with the eastern Isle of Wight, the worst discharge record in more than 300 combined sewer overflows (CSOs) across the wider Solent region. This must surely be a significant causal factor in the harbour’s poor reported environmental health? The 2021 Chichester Harbour Condition Review references only work being undertaken at the Apuldram Wastewater Treatment Works (WwTW) at the time of the study in 2019, presumably successfully since that site is no longer prominent in the ‘worst case’ discharge data.

Were Natural England and its peers at the Environment Agency to work together on addressing the more immediate issues at Southern Water’s assets around the harbour and across the water catchment area, measurably greater and faster benefit could be achieved.

The recommendation presented in 2023’s Royal HaskoningDHV report on their assessment of the Langstone sea wall could be viewed as providing a ‘quick win’ in order to satisfy Natural England. By allowing the paddock wall to fail, indeed by hastening its failure through ‘managed adaptation’, the Chichester Harbour Conservancy would achieve a simple tick in the ‘coastal squeeze’ box. However, far from bringing any immediate improvement to the environmental status of the SSSI and the newly renamed Natural Landscape, the benefit of this relatively tiny example of ‘managed adaptation’ would be barely measurable and certainly far off.

The Royal HaskoningDHV report

The Havant residents’ associations share the common view that the report commissioned for the working group and delivered by Royal HaskoningDHV was given too narrow a brief. In our considered opinion, the resulting deliverable falls short of drawing a balanced and complete recommendation. The brief, discussed in more detail in a previous HCS post, ignored a number of critical factors. Firstly the importance of the local heritage and amenity value, secondly the context of its location at the interface between the various administrative boundaries and perhaps most importantly, lacking any engagement with the affected landowners.

The Royal HaskoningDHV report states, at point 7.4.2, that “The sea wall has failed near Wade Lane creating an area that is vulnerable to unmanaged realignment in the next two to five years. By intervening and creating a managed breach at the location of the failed sea wall, a managed realignment site could be created within the paddock behind the sea wall.” The report continues,“[A] primary goal of managed realignment is to create a new habitat, specifically a saltmarsh habitat, inland of the sea wall.” The report then draws its rather premature conclusion without considering the forces at work on the landward side.

Let’s take a step back

The report appears to assume that the principal cause of flooding in the paddock would be from a breach in the sea wall together with occasional spring tide over-topping.

The reason why the wall collapsed at the paddock / Wade Lane site probably has little to do with any erosion from the seaward side. The root cause of the collapse is far more likely to be the lack of effective maintenance of the millpond, its sluices and the channels of the Lymbourne Stream which feeds it. Indeed, the following picture recently published on the CHC website clearly shows the Lymbourne spring water overflowing the banks of the stream, spilling around the pond and across the paddock to the area of the now well-documented ‘breach’.

With effective maintenance of the stream, the millpond and the sluice, the overflow would be prevented and the ground would be allowed to stabilise. The wall could, and in our view should, be rebuilt as it was, with the drains previously installed by HBC engineers cleared to allow unobstructed freshwater run-off from the paddock in the event that over-topping of the stream becomes an issue in the future. The completely unnecessary cost of solutions involving bridges and boardwalks would be avoided.

The HCS post on ‘Langstone Millpond – ‘Properties and Boundaries’ described the need for regular maintenance of the mill pond and the Lymbourne Stream, as documented in the 1912 Wade Court Estate auction catalogue and included in the sale deeds of the properties bordering the stream. Had the brief given to the Royal HaskoningDHV report’s authors required them to access these readily available sources, they would also likely have concluded that the observed breach has far more to do with the waters of the Lymbourne Stream than it has to do with the waters in the channel between Langstone Harbour and Chichester Harbour. Seen from this perspective, the recommendation for an engineered ‘managed breach’, effectively forcing flooding from the seaward side, appears to some in the local community more like government sponsored desecration of the heritage coastline assets than a carefully considered environmental or coastal defence initiative.

At the December drop-in session, Richard Austin (CHC) commented that in his opinion, the millpond wall where it fronts the dam should be saved and secured, a view also clearly held by Coastal Partners. Where both differ from the local community is in their apparent desire for a managed breach at the south eastern corner of the paddock. As if to rub the point in, the CHC display boards showed not one, but three different photo-montages of bridge and/or boardwalk solutions, each of them costly solution options for a problem that really shouldn’t exist.

If there has to be a breach, then of course we’d need a bridge in order to maintain the footpath, but the question surely is, does there have to be a breach? The only answer on offer from the Working Group seems to be that an engineered breach would enable CHC to report to Defra that restorative action had been taken for the harbour, doubtless without a hint of the irony in that statement.

So why the insistence on a breach being ‘the solution’? Richard Austin commented that the Langstone community is not the only community on the harbour’s eighty-six kilometre shoreline that is looking for consents for repairs to sea walls elsewhere within the boundary of the ‘Chichester Harbour Natural Landscape’ (recently rebranded from AONB – ‘Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty’]). While he is happy to support the call for the restoration of the millpond wall and sluice, the introduction of managed rollback at the paddock wall collapse would conveniently satisfy Natural England and at the same time set a precedent for compromise to other individuals and communities seeking consents for coastal work along the harbour perimeter.

Coastal Partners’ engineers also want the wall fronting the millpond dam repaired and safeguarded but had not seen the three mock-ups in the Conservancy’s images prior to the drop-in session. Their preference would be for a more appropriately engineered and designed, cost-effective bridge over what they see as the potential breach site. It was notable that in the opinion of the coastal engineering team, a natural breach at that point from the seaward side would not occur for many years to come.

So why not clear the pond and the stream, letting the paddock dry out before rebuilding the wall as it was to support this important nationally-recognised coastal path? Contrary to the report’s suggestions, the residents do understand and appreciate that over time the frequency of over-topping of the path and the millpond will increase, as it will in countless places around the shores of the UK. We’re not necessarily looking for higher sea defences and higher availability of access, we’re just looking for nature to take its own course in its own time, without hurrying it along through what might be described as costly acts of environmental vandalism.

Chichester Harbour Investment and Adaptation Plan

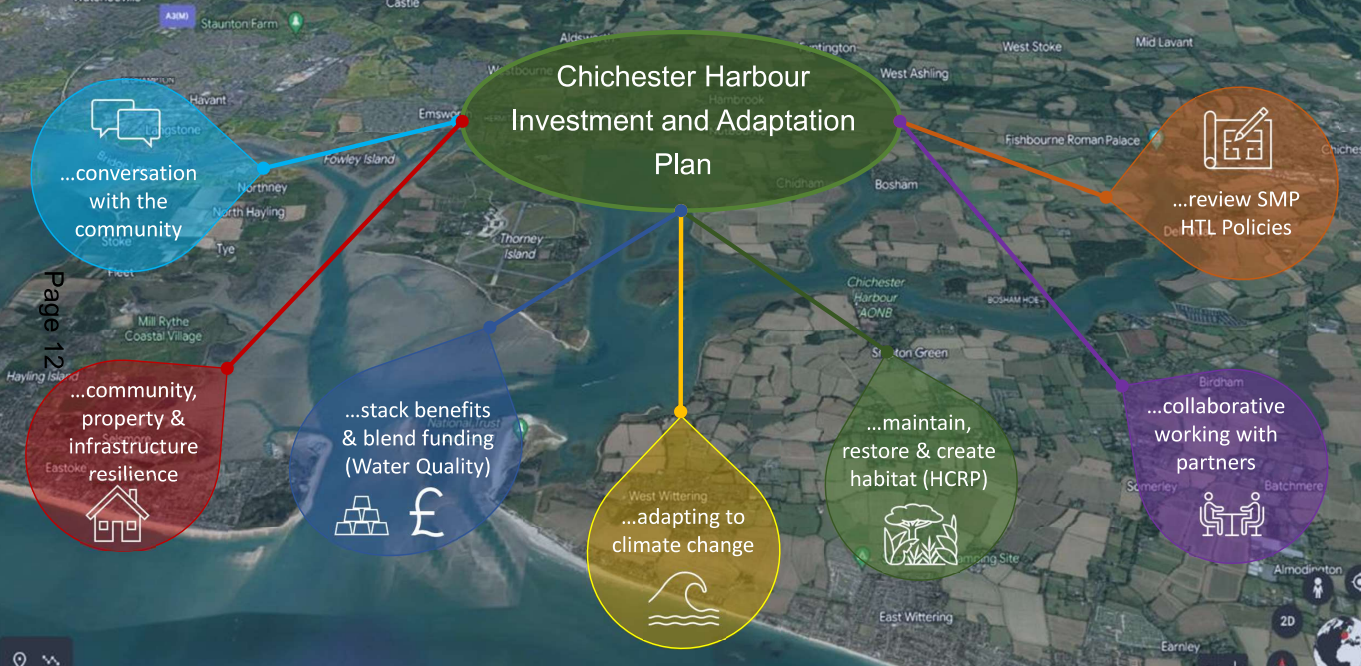

The Chichester Harbour Investment and Adaptation Plan (CHIAP) is an encouraging initiative from Coastal Partners aimed at providing a pragmatic model for governance over the challenge of balancing the harbour’s estuarine health with the need to protect its shoreline’s residential, commercial and heritage assets against the predicted rise in sea levels.

For CHIAP to succeed, all parties must be fully engaged and bought into an overarching governance structure that can secure the necessary functional compromises within a schedule which is being dictated by nature itself. The work will involve engagement and teamwork between central and local government authorities, commercial organisations and the residential and small business communities which live and work around the harbour’s catchment area.

Progress will be hindered if the central government agencies get unnecessarily drawn into local minutiae:

Maintaining long-established sea defences over, for example, a 200m stretch around the millpond and paddock at Langstone will clearly make no immediate or measurable difference to the overall health of Chichester Harbour. In this case, it would surely be more sensible for the local authorities to have delegated authority over, and accountability for, the right local solution. A process which positions Natural England as the final arbiter is, in this case, unproductive and unhelpful, causing an unreasonable waste of time and resources.

On the other hand, improvements to the volume and quality of effluent entering the harbour from locations already known to the Environment Agency, will clearly have a significant and immediate benefit. In this case, Natural England, backed up by the Environment Agency with its regulatory role, should and must take clear and unambiguous authority and accountability for the solution and the necessary actions.

The priority for any solution and the recommendation for appropriate delegation should be left to Coastal Partners, assisted by an apolitical panel of subject matter experts drawn from the local authorities, the Environment Agency, Natural England, affected large commercial businesses and selected representatives from the local business and residential communities which form the harbour’s population.

Those communities and their accountable local authorities need to work together while the central agencies need to focus on the availability of funding and delivery resources. Responsible commercial businesses such as Southern Water need to demonstrate their accountability by providing a level of match-funding as mitigation for the impact their business has on the environment of the harbour. That latter point is where the Environment Agency and Natural England can really add value by ensuring that funding contributions are received from accountable parties.

Thinking outside the box

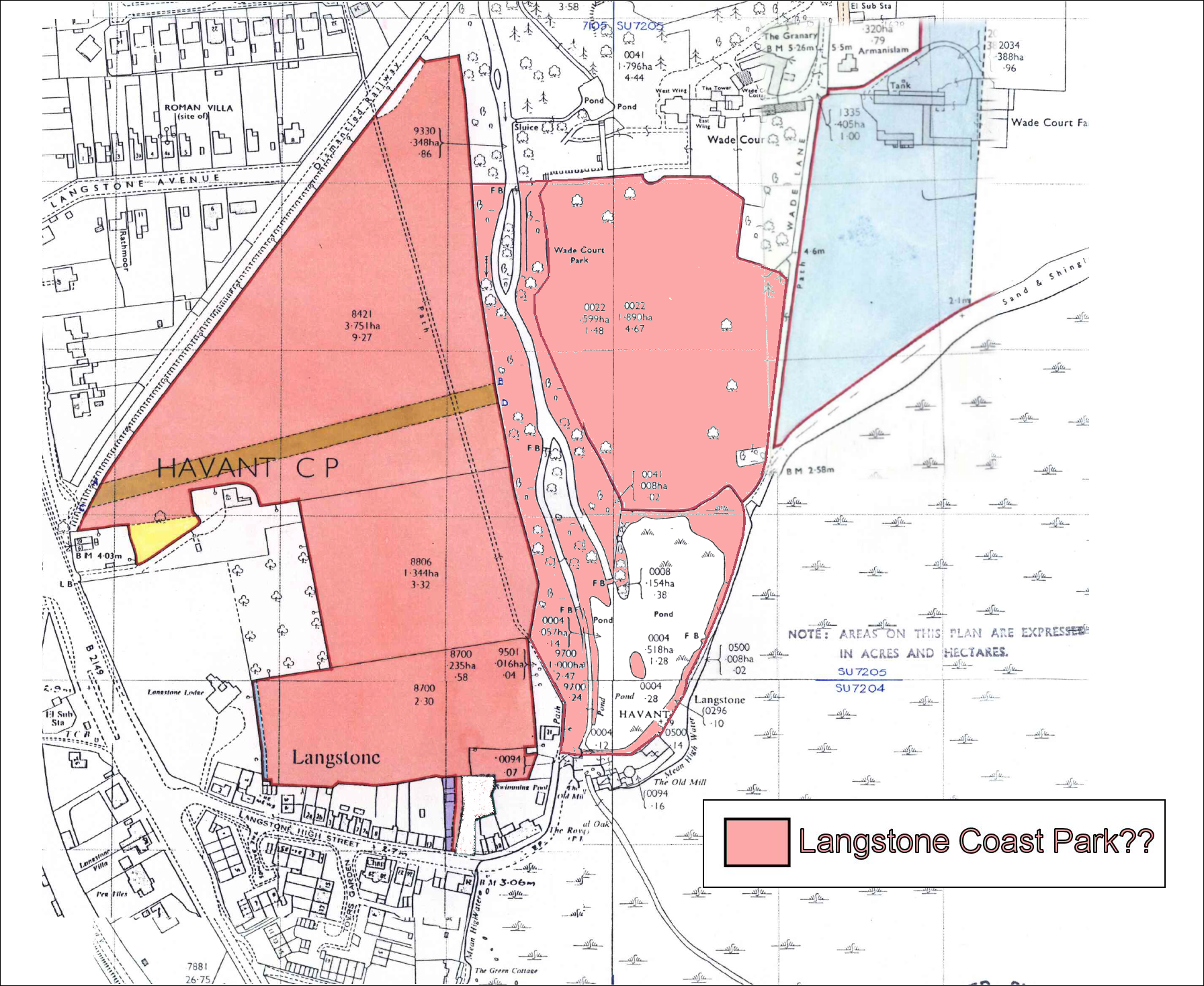

Hampshire County Council and Havant Borough Council might consider exercising a little lateral thinking and examine whether a different approach might be taken for the future of the Langstone heritage shoreline.

If the current owners of the millpond and the paddock are unable to perform the maintenance activity which would stabilise and secure those two land assets, then perhaps compulsory purchase could be used to bring both sites under council ownership. With the current parlous state of the assets, the price would likely be low and once under local authority ownership and working with Environment Agency resources, the Lymbourne Stream, the pond and the paddock could be returned to a healthy state with an effective and reliable maintenance regime in place.

In summary

Lyall Cairns (Coastal Partners) struck a chord at the HBC Overview and Scrutiny session on 7 December when he said “I don’t want to do more studies. I think we’ve got all the studies and evidence that we need to make better decisions. What we haven’t had is joined-up conversations across all the sectors [and] all the interested parties to value our heritage and landscape and make better choices.”

Climate change is far from new, I first studied its effects over fifty years ago. What is new is that we’ve finally faced up to the need for climate change adaptation given the realisation that the clock is ticking. We all need to stop resisting and start pulling together. The Chichester Harbour shoreline residential and small business communities – including the Havant residents’ associations – should be invited to engage directly with the CHIAP initiative, contributing to and working with the adaptation plan, rather than fighting against it.

The Chichester Harbour Investment and Adaptation Plan could set an important precedent to the Defra bodies, Natural England and the Environment Agency, by providing local authorities, large commercial businesses and the residential and small business communities around the UK coastline with model process for addressing climate change adaptation.

Perhaps the hardest group to bring into line is also ultimately the most important, the general public; the communities which surround the harbour. Those communities need to buy into the approach with a single voice and that means that individual villages, hamlets and properties bordering the shoreline may have to swallow some pride and share some cost. If we all keep arguing across each other, we’ll just end up running down the clock. If the government agencies insist on hiding behind fixed rules, no optimal solution will be possible. If local authorities and parish councils don’t adapt to the new set of rules, then they too will lose the confidence of their residents.

The next meeting of the ‘Working Group’, (Coastal Partners, Natural England, Environment Agency, Chichester Harbour Conservancy) will have the opportunity to either turn things around or turn things upside down. In order to achieve a satisfactory outcome, I would suggest that direct representatives from the residents’ communities should be included.

BC – 30 December 2023