Introduction

On 14 May, we posted an article highlighting the campaign to save Langstone millpond. It is a campaign which has raised understandable alarm within the local community and one which has now focused the minds of the HBC leadership team, fearing another difficult election year in 2024 following the upcoming boundary changes.

The subject of concern is the precarious state of the brick sea wall which protects the seaward face of the millpond’s old earth dam and provides the foundation for a particularly scenic part of the public footpath from the bottom of Wade Lane to Langstone Mill.

Local residents believe that without urgent action by the relevant authorities, another winter will see the path gone, the dam breached and the millpond abandoned to become a tidal swamp, changing the shoreline forever and destroying this unique and much loved local wildlife reserve. That timescale might be an exaggeration, but it’s abundantly clear that the millpond wall is long overdue a little care and attention.

At this point it’s worth taking stock of the bigger picture. This is not the first time that the wall has failed and once again, the local authorities – both at borough and county level – need to come up with a pragmatic solution in order to win the support of the residents and maintain a much loved and valued local heritage and amenity asset.

Forty years ago, when significant repairs were last made to the wall and the footpath, it was a relatively straightforward matter for Hampshire and Havant to resolve without any interference from central government. Roll forward to 2023, however, and we appear to be up against the Department of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and its thirty-odd ‘non-departmental public bodies’, not the least of which are the Environment Agency, Natural England and the Marine Management Organisation. Legislative actions by both the UK and European parliaments have set up a mosaic of designated protected areas which, while well-intentioned and without doubt valuable, provide clumsy instruments for resolving an issue with just 200 metres of sea frontage.

This article takes a longer view and attempts to draw together the various threads relevant to the discussion and suggests a pragmatic solution to an old problem.

- The ‘Climate change’ perspective

- The Langstone millpond perspective

- The Southmoor perspective

- The Chichester Harbour perspective

- The ‘Southern Water’ factor

- Accountability and responsibility

- Further reading

The ‘Climate change’ perspective

The need for climate change adaptation triggers something of a Catch-22 situation in coastal communities. As the sea level rises, nearby homeowners and businesses demand improvements in flood defences. However, building sea walls in fixed positions means that the rising sea has nowhere to go, the seashore in front of those walls will become narrower, eventually disappearing. The loss of intertidal habitat through sea level rise and its consequent impact on ecology at a fixed shoreline is referred to as ‘coastal squeeze‘.

Coastal habitats will naturally adapt to a changing climate by migrating inland, but in highly populated areas like the Solent there is little room for this process to happen as much of the coastline is dedicated to commercial or housing use. Where the importance of business and number of homes threatened dictates, the cost of continued and enhanced defence is justified.

Habitats such as saltmarshes and sand dunes act as natural coastal defences and their loss will lead to increasing pressure on man-made defences. One of the most important issues for the Solent’s coastal planners and managers is how best to protect the coast for human use whilst allowing for the retention and movement of wildlife habitats as sea level rises and wave conditions change.

Shoreline management plans have been developed by administrative coastal groups with representatives mainly drawn from local councils and the Environment Agency. They identified the most sustainable approach to managing the flood and coastal erosion risks to the coastline in the short, medium and long terms. Coastal Partners, based in Havant but working across a consortium of local authorities, is the organisation responsible for defining the action plans for the climate change adaptation for shoreline across our region, assigning the following designations according to a UK government defined cost-benefit assessment:

‘Hold the line‘ (maintain the existing coastline)

‘Advance the line‘ ( build new defences out from the shore)

‘Managed realignment‘ (enable controlled roll back)

and

‘No active intervention‘, (do nothing and let nature takes its course).

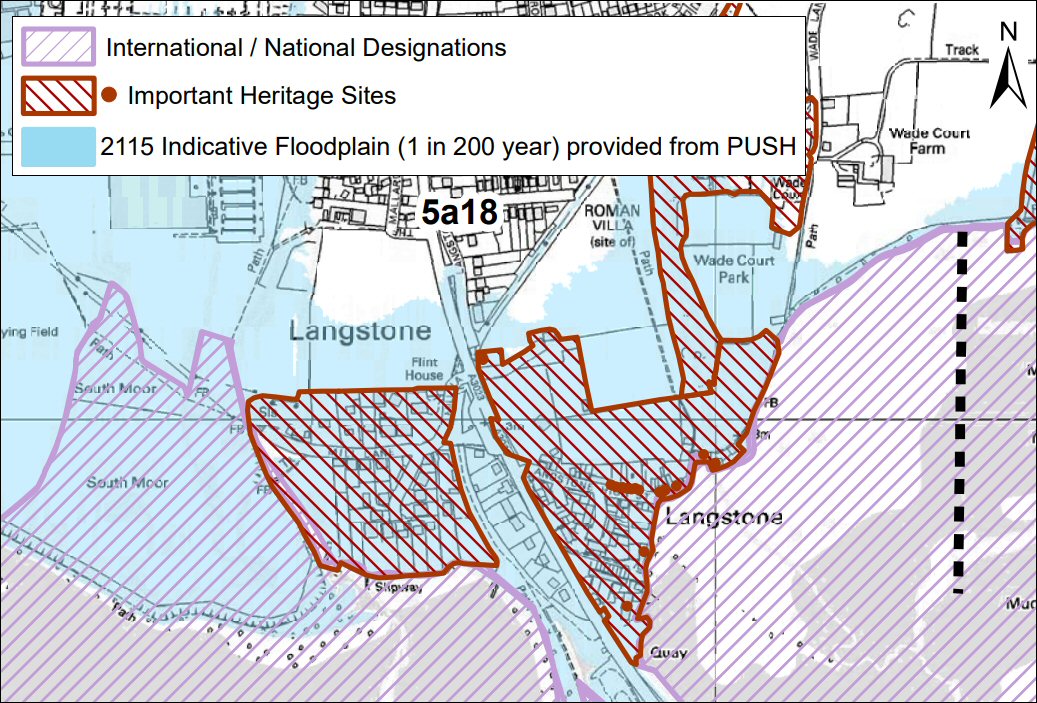

The North Solent Shoreline Management Plan (2010, last updated in 2022) designated the entire coastline between Wade Lane and Southmoor Lane (Policy ref. 5A18) as ‘Hold the line‘, while noting that “further detailed studies are required which consider whether ‘Managed realignment’ may occur at Southmoor”.

The original shoreline management plans have evolved over time. Rising construction costs and competing priorities inevitably mean that ambitions have been modified and as the shoreline change at Southmoor demonstrates, the intention to hold the line across our region’s coastline has clearly moved on leaving sites such as Langstone millpond ‘orphaned’, left exposed with no planned solution.

It is likely that locally orphaned coastal defence situations across the Solent area will find themselves in competition for limited availability of suitably-skilled coastal engineering and design resources, even if those projects can be fast-tracked through the local authority administrative processes. At the heart of the matter for these local projects is the question of whether the local situation reflects the national challenge that the authorities have over how society values and responds to climate change. Do the general public recognise and value a need to prioritise protection and enhancement of the environment? With limited funding for the maintenance of ageing assets and a shift in policy relating to coastal matters from a ‘presumption to defend’ to one of adaptation, this presents a significant challenge, both nationally and locally. The government, through Defra and its agencies, have determined national policies and directions. Local government needs to engage with local populations to debate and prioritise funding of local exceptions.

The long term impact of man-made global warming has been understood for decades. As an undergraduate fifty years ago, I wrote a dissertation on the ‘Greenhouse Effect’, quoting as sources, academic papers written up to twenty years earlier. Scientists and engineers have long known that this would happen, but until society values and responds to climate change with the priority it deserves and recognises the financial sacrifices that will be required to make the appropriate adaptations to our coastal environment, the scale of the challenge will only increase. This will affects all coastal communities throughout the estuaries and harbours of the Solent, not just in Langstone, and the relevant local authorities, supported by their local MPs, will need to take the fight to Defra on behalf of their communities.

The Langstone millpond perspective

The subject is, without question, the most sketched, painted and photographed corner of the borough of Havant. The Royal Oak and Langstone Mill have been significant local sites for the past three hundred years and, thanks to the many overseas staff who worked in the borough during Havant’s manufacturing heyday, framed memories of this scene can be found in homes around the world.

The term Langstone Mill is probably seen by many as a singular reference to the old black structure of the windmill. Less obvious is that Langstone is possibly unique with its combination of both a windmill and a tide mill on the same site.

Built around 1800, the tide mill operated two ten foot wheels, one set higher than the other to make full use of the stream feed and the tide, which was kept back behind tide gates. The more distinctive black windmill is an earlier structure, dating from 1720 – 1740. The Historic England listing record describes “a close group of three parts, comprising a water mill (tide mill) and a mill store (now a dwelling) attached to a windmill (part of the dwelling). Early 19th century. The water mill is built across a creek and is associated with a sea-wall with sluices.”

Tucked away behind the mill is the millpond, a destination well known to bird watchers, local families and the many passing hikers on the England Coast Path. It is a peaceful and beautiful haven which in recent years has become home to the largest colony of little egrets on the south coast of England, recently joined by nesting pairs of cattle egrets.

Look behind the tranquillity of this scene and all is not well. The millpond is contained by a simple earthen dam which also forms the foundation of the walk Havant residents have enjoyed for the past couple of hundred years.

The current millpond is a 2.9 acre natural reserve for wildlife. Its unique environmental feature is that its waters occasionally become saline when some combination of Spring tides, low pressure, and south-easterly storms cause the dam wall to be overtopped. The pond is subsequently refreshed with fresh water from the Lymbourne Stream making this a large and unusual intertidal habitat. Usually such intertidal habitats are found on the fringes of estuaries and drain on every tide whereas the sea wall at Langstone millpond permanently retains the pond water, occasionally becoming saline but regularly refreshed by the incoming, chalk-fed spring water from the Lymbourne Stream. This unusual phenomenon provides a habitat which is rare in the UK.

A recent Chichester Harbour Conservancy ecology report notes that the Langstone millpond and paddock have been designated as a Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINC) while some of the woodland to the north, Wade Court Park, is a separate SINC. Three components of these sites are listed under Natural England’s priority habitat inventory‘, the woodland as ‘deciduous woodland’, part of the reedbed area as ‘reedbed’, and the entire paddock as ‘floodplain and coastal grazing marsh’. These important local sites lay adjacent to the Chichester Harbour Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), Chichester and Langstone Harbour Special Protection Area (SPA) , Ramsar site and Solent Maritime Special Area for Conservation (SAC). (A Ramsar site is a wetland site designated to be of international importance under the Ramsar Convention, December,1975.)

The inclusion of the millpond and paddock in HBC’s Langstone Conservation Area, recognises the importance of the mills, the millpond, the dam and sea wall as an integral part of this important heritage site.

Seen from above, the 200 metre dam, stretching between the old water mill building on the left and the southern end of Wade Lane on the right, is the retaining structure which maintains the level of water in the millpond. The Lymbourne Stream enters the pond from the north, draining via the tide gate under the old watermill building and the sluice midway along the wall.

In recent years, the intensity of seasonal storms has left the earth dam exposed in places with the sections of the sea wall in various states of collapse. Only last year, a memorial bench placed as a testament to happier days had to be removed from the most immediately vulnerable section close to the bottom of Wade Lane. Climate change will inevitably increase the intensity of those storms and the consequent sea level rise will increase the amount of time in each tide that the wall will be subject to wave action.

At the date of this article, the whole length of the sea wall fronting the millpond is in a serious state of disrepair. With no funded and coordinated programme of maintenance, the dam is becoming increasingly exposed to the elements and vulnerable to erosion. Without active intervention, the wall will continue to deteriorate, allowing the earth of the dam to slip downward and outward, undermining the footpath. Without timely repairs to the sea wall, the core of the dam will be exposed and the risk of a breach will increase. Should the dam breach, then the damage to the currently stable environment of the millpond would probably be unrecoverable.

This is not the first time in its recent history that the sea wall fronting the dam has needed attention. This local press report from May 1982 documents a previous campaign to save the footpath with an apposite comment from the late Ray Cobbett on the value of the task. History, it seems, is repeating itself.

The integrity of the whole dam depends on each of the component parts since failure on either side will undoubtedly weaken the structure. The questions are, to what extent and over what timescale?

Representatives of the Langstone Village Association believe that a catastrophic failure of the dam itself could happen as soon as the coming winter if the wall is not replaced or repaired. Coastal Partners, on the other hand, comment that “Rapid and dramatic breach is unexpected, there are already defects present in the wall. Should the noted defects collapse we expect the rate of erosion will vary year to year depending upon the severity of the winter, but would estimate approximately 0.1m per year.” This view from professional coastal engineers offers encouragement that there is adequate time for further detailed assessment to be undertaken but it does not suggest that nothing should be done.

If the construction of the dam follows accepted principles, it will have at its centre, a non-permeable core, probably formed with clay, banked up on either side by compacted soil and rubble. On the millpond side, a further clay coating prevents the pond water from permeating the dam while on the seaward side the brick wall structure provides some level of protection for the earth bank from erosion by wave action at high tides. Judging by the newspaper article above, the wall – which some sources describe as ‘Victorian’ – has been patched and partly replaced on several occasions in the past, most recently forty years ago.

The Southmoor perspective

There are fears that the failure of the wall on the seaward side of the millpond’s dam wall might in time emulate the failure of the wall at Southmoor, a few hundred metres away to the west of Langstone bridge. Take a look at the image below which shows the millpond on the far right and the field at Southmoor on the left. Click through the arrows or swipe left on the image to see the impact of the September 2020 Southmoor sea wall breach, noting the dates at the bottom left.

The poor condition of the Southmoor wall had been recognised well in advance of the breach and the Environment Agency had developed plans for its ‘managed realignment’ in 2017. In the design of that project, below, a planned breach would have been made at the weakest point on the wall to create a new coastal wetland. This was the point at which the tide eventually broke though during storms in October 2021.

The planned ‘managed realignment’ had not been progressed due to concerns about the underground utility services to Hayling Island that run across the site and within the space of four winters, nature had taken its course. The lack of active intervention at Southmoor means that the flood defence bund at the planned northern perimeter of the new tidal lagoon was never built and the coast path has yet to be re-established, leaving an unsatisfactory temporary diversion in place. The cost of rectifying this would undoubtedly exceed the original £800,000 estimate for the abandoned project.

Taking a positive view, the new Southmoor lagoon will in time mature into a new biodiverse wetland which should also add value to the local amenity. The result of the natural breach can be seen in the RSPB drone image below, taken at high water in October 2022, just one year after the event.

A direct comparison between Southmoor and the Langstone millpond is not straightforward since the engineering and construction of the old Southmoor sea defence will differ from that of the dam with its rather rudimentary brick wall protection at Langstone. The coastline at Southmoor has a significantly higher level of exposure to south westerly storms than the more protected shoreline at the millpond, but the Langstone dam had an additional lateral pressure from the contained water in the millpond. The forces acting on the two walls are quite different and any prediction of risk of failure at Langstone based on Southmoor experience is probably unsound.

Allowing Southmoor to ‘roll back’ has contributed positively to the health of Langstone Harbour and will in time, and with appropriate investment by the relevant authorities, could increase the value of the public amenity offered by the Havant borough shoreline, with no loss to heritage assets. In contrast, allowing ‘unmanaged realignment’ to accelerate the erosion of the Langstone dam, will destroy an existing and long established local wildlife asset, leaving a mess which will take many years to stabilise. When the dam eventually breaches, estimates suggest that 15,000 tons of water and silt will be spilled into the Chichester Harbour SSSI, leaving behind a tidal environment in which the level of the former millpond would vary by well over a metre with each tide.

The Chichester Harbour perspective

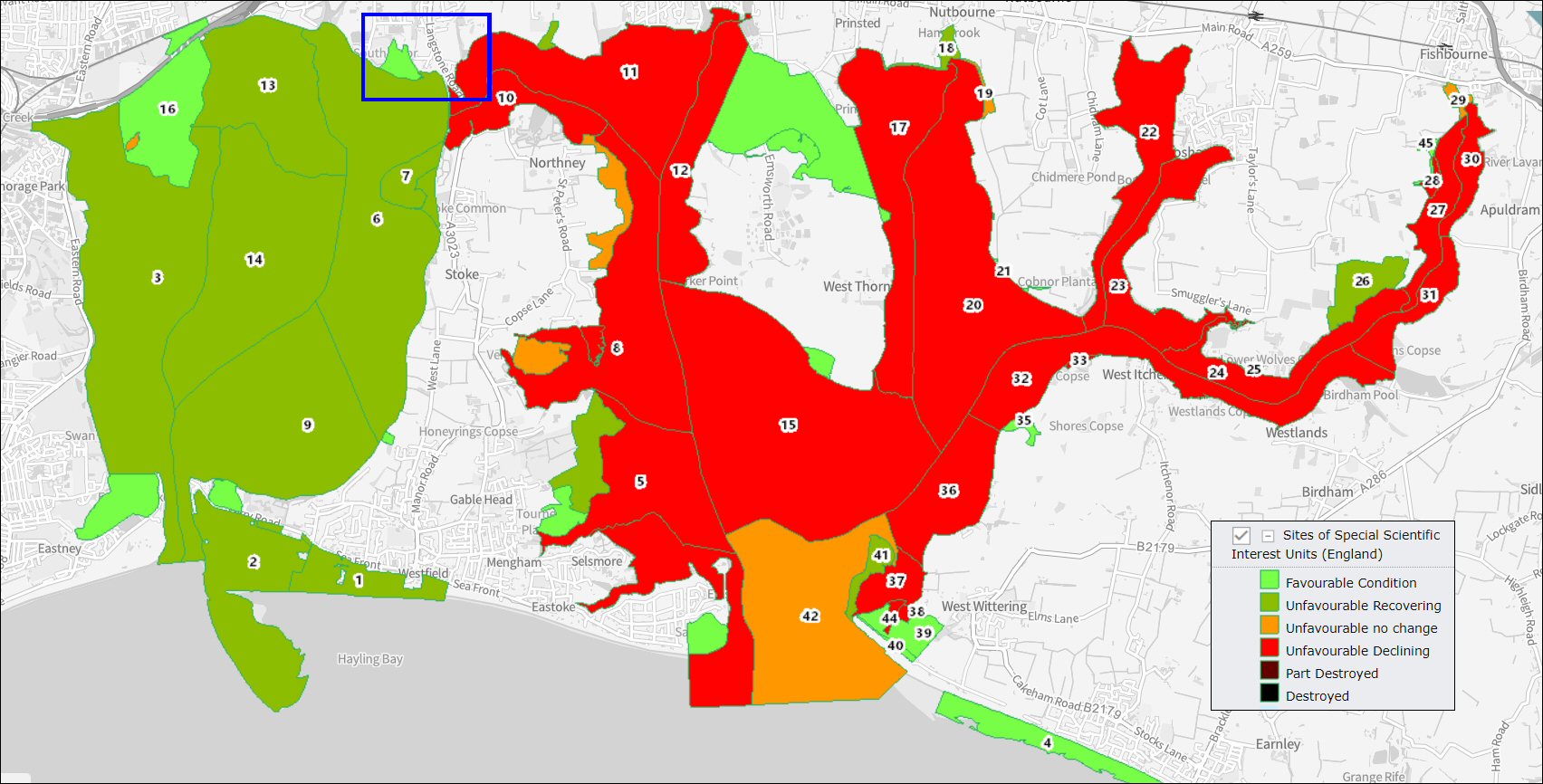

Chichester Harbour is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful harbours in the UK, viewed either from the sea or from its extensive shoreline. Langstone Harbour would on the face of it appear a smaller and poorer relation. Take a deeper look at both, however, and a comparison of the environmental health of both waterbodies shows marked differences. Both harbours are designated as Sites of Special Scientific Interest and the following image from Defra’s data mapping source offers a quick snapshot of the difference.

Chichester Harbour is now seriously declining in environmental health, while Langstone Harbour is recovering well and at Eastney Lake, the Kench, Farlington Marshes and the new Southmoor RSPB reserve, is classified as ‘favourable’.

Looking at the area within the blue rectangle in that previous chart, the following slides show Southmoor and Langstone millpond within the broader context of Chichester Harbour. This highlights the fact that the length of the millpond wall, at 230 metres maximum, represents barely a quarter of one percent of the 86 km of Chichester Harbour’s coastline.

Prior to the May 2023 HBC election, the policy of the council was that the defence of the millpond as a local habitat, including the protection of its heritage and amenity value, was less important than the blanket argument that coastal squeeze was a ‘Bad Thing’ and the ‘Roll Back’ was the only answer. There was no willingness to challenge Defra with the obvious argument that the 230 metres of new ‘roll back’ at Langstone will make little or no difference in the wider context of the Chichester harbour coastline. The loss of local habitat, heritage and amenity value to the Havant borough coastline, however, would be significant.

The ‘Southern Water’ factor

For the past three years, Solent Protection Society has extracted and analysed the Environment Agency annual data on storm overflow releases into the Solent. The data shows that there are some 300 Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs) discharging into the Solent either directly, or indirectly via the harbours and estuaries particularly, with these spills usually occurring after even light to moderate rainfall . Further analysis shows that more than 70% of these discharge hours were related to around 30 identified CSOs for which priority for urgent action has been suggested to Southern Water.

Based on the 2020 EA data, SPS divided the Solent into 15 areas, identifying the 34 overflows in these areas that were most critical. All these areas either affect bathing beaches or marine leisure activities as well as environmentally sensitive marine protected areas. The worst performing individual overflow was Chichester WTW 2 SSO (sanitary sewer overflow) with over 2600 hours of spilling; the equivalent of discharging continuously for over three and a half months in 2020. The worst region in the 2020 data was ‘Isle of Wight East’, covering Ryde, Bembridge and Sandown.

It is notable that in the 2021 and 2022 EA data, the region of ‘Chichester Harbour’ has now taken the unwelcome top spot, thanks to the record of discharges at five main overflows: Bosham, Chichester, Lavant, Thornham, and Nutbourne.

While the Chichester Harbour Conservancy ‘Condition report’ contains a few comments about improvements being made at Southern Water sites around the harbour, it is not clear that the true scale of the company’s discharges from those locations are understood. It is likely that increased investment by the company at these sites would provide significantly greater benefit to the health of the Chichester Harbour SSI that simply enabling 230 m of unwelcome roll back on the Havant shoreline.

Accountability and responsibility

The sea wall is not registered as the property of the owners of the mill, nor is it an asset registered to the Chichester Harbour Conservancy, whose responsibility includes the intertidal zone in front of it.

Since there are no homes at risk of flooding behind the sea wall, the Environment Agency and Natural England, both non-departmental public bodies sponsored by Defra, have neither responsibility nor legal obligation for the maintenance. Significantly, they also deny any justification for the use of ‘Flood Defence Grant in Aid’ funds for this purpose. (It is that aid program which is underwriting the massive sea defence work seen around Portsea Island.)

Hampshire County Council is responsible for the management of the public’s right to access and use the public footpath, but has no legal responsibility for maintenance of the sea wall.

A Langstone Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management (FCERM) Scheme is currently being developed by Coastal Partners to reduce the flood and erosion risk to the community, important heritage assets and the A3023, the single road access to/from Hayling Island. Following extensive option, environmental and economic appraisal, replacement of the defences fronting the millpond were deemed not financially viable and therefore are not part of the proposed scheme at Langstone.

Havant Borough Council has permissive powers under the Coast Protection Act 1949 to undertake “any coast protection work, whether within or outside their area, which appears to the authority to be necessary or expedient for the protection of any land in their area.” However, it appears that the current approach by HBC and HCC is to cover only land on which home or business properties are at risk, ignoring the obvious potential for loss of heritage, amenity and locally designated habitat. The local authorities appear also to be suggesting that no central funding can be made available to protect against such a risk, whereas it appears that the Environment Agency may be able to make grants available to local authorities for such work under the Flood and Water Management Act 2010, with conditions as to repayment.

Before the recent election, HBC’s stated position accepted a blanket high-level argument by the Secretary of State responsible for Defra that “It is more likely than not that the opportunity to rollback would produce a healthier saltmarsh of more variable composition, which would enhance the quality of the protected sites”. That argument is undoubtedly true in the overall context of the 86 km shoreline of Chichester Harbour, where 25 km is already free to rollback, but it’s hardly a convincing argument for abandoning the 200 m stretch of sea wall which protects the millpond and the paddock. HBC could justifiably argue that the unmanaged realignment at Southmoor has already added three times that length of Langstone Harbour coastline in mitigation. Since Havant straddles both of the geographically-linked harbours, it could argue that the two SSSIs could be considered together.

The overriding fact is surely that the millpond is a fundamental part of one of Havant borough’s premier heritage and outdoor amenity assets – free of charge to all. It’s an asset which punches well above its weight to a world-wide audience. As a natural branch from the Billy Track and an integral section of the Wayfarer’s Walk, the dam and the sea wall form a well-known and well-trodden coast path and cycle route which the families of local residents and visitors have enjoyed for generations.

The way forward

The campaign team was encouraged by the news that on 15 May, Chichester Harbour Conservancy issued a tender to seek quotations from external consultants for “A feasibility study relating to Land at Langstone, Chichester Harbour”. (Click the link to view the comprehensive specification prepared by CHC.)

This needs to be tempered by the fact that it will only report in October. etcetera…

With no clear ownership identified for the failing structure and an apparently inflexible direction from Defra that nature should take its course, Havant Borough Council’s erstwhile cabinet maverick declined to challenge the secretary of state’s line and promptly lost his seat in the May local election.

Wise to the fact that the Langstone millpond issue will provide an election call-to-action in 2024, the leader of the council accompanied by his new cabinet lead for coastal matters, embraced the cause and joined a local protest march by the ‘Save our Pond’ campaign,

Stuck in the middle, while some at very local levels might disagree, Coastal Partners are doing a solid job of ensuring that the right coastal engineering solutions are being delivered for the areas within the priorities set by Defra for funding. With so much of the Solent shoreline at risk from sea level rise, sacrifices will inevitably have to be made and that’s where HBC need to step up, with the support of the borough’s MP, to fight the case for the millpond. That fight will only be won when the heritage and amenity cards are played together with the local habitat card.

The opinion previously put forward by HBC representatives that the ‘advice from Natural England is clear’, effectively that ‘do nothing’ is the only option, is in our opinion, wrong. That decision would condemn one of the borough’s most important environmental, public amenity and industrial heritage assets to the history books, taking with it a locally important, globally appreciated tourist site.

These are complex arguments and with constraints on funding there seems a lack of will on the part of the authorities to fight for a long term solution which will preserves Langstone’s heritage, habitat and amenity in balance. We would encourage concerned residents to write to our member of parliament, Alan Mak MP, copying Cllr. Alex Rennie as the leader of Havant Borough Council and your local ward councillors, calling for a concerted effort to push back against the Secretary of State for Defra and argue the wider case for investment in a properly thought out solution.

If all else fails, then there are local precedents for community-driven sea defence work. You only need to look a little further round the same shoreline to see the work undertaken by the ‘Friends of Norebarn Woods’. The problem they needed to solve was rather more straightforward and the ownership of the land was not in dispute – it was Havant Borough Council. Times and scientific thinking have now moved forward and with a necessary focus on the effect of sea level rise on the entire coastline, any local ‘small scale’ project would need to take into account its relationship with the land and the shoreline on either side of it.

Immediately east of Wade Lane, the England Coast Path follows the shore – already inaccessible at high water spring tides – and the only sea defence there is provided by a line of vertically-stacked railway sleepers recycled from the Hayling Billy line. Since the current Environment Agency coastal erosion risk map shows the strategic direction for that section as ‘Hold the line’, perhaps that would be a better use for the ‘recycled plastic boardwalk’.

Havant Borough Council need to set aside party politics and address the issue of this relatively tiny section of sea wall at the millpond as a local community project. The Defra ‘coastal squeeze’ and associated ‘rollback’ direction should be ignored. Given the small scale of coastal squeeze

Further reading

A summary explanation of coastal squeeze can be found here, and a detailed government report can be downloaded here.